4 Steps to Better Off the Ball Movement

Confession time…

As a coach, I find off the ball movement to be one of the most challenging areas to develop.

That’s not to say I don’t have a clear idea of what I want to see or what I would do in a given scenario.

It’s that…well…coaching such a context laden topic is difficult. The context of the game is constantly changing. New realities emerge, then disappear in an instant.

But, as Johan Cruyff said, “soccer is a thinking game and the feet are the tools.”

It’s far too easy to focus on the tools of the craft rather than the craftsman, or the ideal we would like to see rather than the chaos and constant change of this dynamic sport.

Soccer is a game of decisions.

Simple decisions can produce results, as any hit-and-hope team can tell you, but there’s something very unsatisfying in that style. Maybe it’s the distinct lack of style that’s so bothersome. In a game of ideas, it de-emphasizes the core of the sport. It’s born of fear or ignorance rather than courage or intelligence.

There is a time to simplify tactics, don’t get me wrong, but it's…it's so unsatisfying.

One other issue is how difficult it is to play constructively. Make a bad pass, boom, the chance is gone. One bad touch and, abracadabra, the opportunity has disappeared.

Maybe that’s one of the difficulties with coaching possession dominant sides. There’s so much patience required. When your side puts in a lot of work to progress the ball, it’s easy to develop a sense of entitlement that the play should be rewarded. I’ve been there and still make the occasional (probably frequent) visit back to that state.

But those failed possessions or games against teams that blow up a 20-pass sequence with one big boot up the pitch bring us back to the reality of the game. Possession-based dominance is difficult. Plan as you like, but that 20th action could set you back at square one.

It’s humbling, requiring perseverance and an active mind. We’re called to learn from our setbacks and go again, looking to correct the one mistake that doomed our last sequence.

As coaches, it’s also a reminder that proactive, attacking play means we’re placing the onus on our players to dominate the run of play. Our sessions must then develop the intelligence, creativity, and character of our players.

Introducing competition at each possible point in the practice is a great start. The decisions required in games offer the perfect learning opportunities. Know what you’re looking for and you’ll also find the right moments for teaching.

That’s the topic of this article.

THE 4 STEPS OF OFF THE BALL MOVEMENT

So why is off the ball movement so difficult to coach?

Probably because we start at the wrong place. Or maybe we challenge our players to find space or check their shoulders, but then that’s the end of the conversation. We have “whats" but not “whys” or even “hows”.

Coaching off the ball movement requires a sequence of coordinated actions with cognitive fidelity to ecological dynamics. There’s an aspect of structure provided by the team’s game model and matchup specific tactics, as well as the freedom of action players exercise within their roles. Within the limitations of the role are the freedoms to take action with a greater understanding of optimal possibilities.

But you can take what you can’t see. You can’t explode into action when you’re unprepared for it. You can’t exercise influence without understanding how to impact the game.

So how can we have these conversations with our players and help them develop a greater sense of awareness on the pitch? There are a few models available online, the best of which is Todd Beane’s Cognitive Wheel, which uses a rich vocabulary with succinct terms, but I’ve simplified it even further for my players. When speaking of off the ball movement, we talk about 1) finding the space, 2) filling the space, 3) correcting body orientation, and 4) connecting actions. Here’s how I use these simple ideas and relevant examples from elite players.

Find the Space

Finding space is a matter of vision and awareness.

This is where most players get it wrong. Even at the pro ranks, you’ll find players who get this wrong. Some still struggle with the poor habit of tunnel vision on the ball, whereas others have progressed beyond that pitfall only to struggle with the “when” of scanning.

Dr. Geir Jordet’s work on scanning is a must-follow for anyone seeking to help themselves or others in better visual perception habits. This brief YouTube video shows some of the nuances, but there’s so much more research available through his website and social media pages.

Getting the how, when, and why of scanning can be a slow process. Players will often focus on the wrong sensory data or choose the wrong time to scan. There’s an undeniable rhythm to scanning that comes with a learning curve. The sooner we work on scanning, the sooner we help our players be more deliberate with their focus and to develop ideas before they receive the ball rather than reactively waiting for the ball to arrive at their feet, then mentally engaging.

Continuously updating the mental image of the pitch is a full-game task, but looking isn’t enough. Contextualize! Always contextualize!

Easier said than done, right?

Yes, but we have a helpful tool, our language, to help us discuss scanning. When we speak to our players about finding space, that space must be in relation to the four reference points.

- Ball

- Teammates

- Opponents

- Space

Here’s a helpful visual from The Soccer Parenting Handbook.

Discussing the four reference points helps players to understand that their positioning is always relative to other influences in their environment. Distance from the ball impacts your spacing in relation to teammates, which is something I call layers of possession. I touched on this in a past Total Football Analysis article called, “Coaching: Training Purpose and Cues with Layers of Possession” (be sure to follow me on Twitter @CoachScottCopy for an upcoming thread on this article). Add in the dynamic presences of opponents and you have limited spaces to take up. Awareness of the player’s environment limits options, which streamlines decisions.

Selecting the best possible space in relation to the ball, teammates, and opponents is the final step. The guiding principle here is that the selected space should attempt to establish a superiority, either for yourself or a teammate.

If you’ve forgotten the four superiorities or are unaware of them, here’s the list.

- Numeric

- Qualitative

- Positional

- Socio-Affective

Movements off the ball and possession should establish at least one of these superiorities, if not multiple. Numeric is fairly straightforward, having more players in an area than the opposition. So is qualitative, where you're simply better than the opposition. Socio-affective is a superiority in which your players near the ball have a better understanding of how to work with each other than the opposition's players do. Positional is the most difficult to define, but it's one of those where you certainly know it when you see it. In simple terms, it's having players in a better position than the opposition in respect to a specific scenario.

As players scan the pitch to "find the space," their minds should take into consideration both the four reference points and the four superiorities. It's a proactive way of engaging the game, and also the one most likely to bring success. Using reference points to establish superiorities is a way to keep our players engaged and hunting for small advantages.

Fill the Space

Once players have identified the optimal space to move into, the next step is fairly simple.

Move.

Now, the way to add nuance is to train players how to move into those spaces and why the timing and disguising of intent are so important. One phrase I like to use is "create the space you want to attack." That might include dragging an opponent away from that space, delaying a run to the last possible moment to keep that space open, or even coordinating movements with teammates to create space (like we see when teammates temporarily switch positions or roles).

We get an example of this with Borussia Dortmund's young star, Erling Haaland. In the image below, it's pretty clear the space he wants to attack is at the far post. However, he can't simply run into that space. A straight run is too easy to track and his defender, who has the inside blocked off, would easily clear the ball. Instead, we see Haaland driving his mark towards the near post on a diagonal before making his cut to the far post.

Notice the timing in the sequence. The cross is not yet on its way, so he uses these precious seconds to delay his run to the far post while also taking his opponent away from the space he wants to attack. There's also an excellent counter move, peeling away from his defender, whose momentum is taking him to the near post. Moving against the defender's momentum is one of the easiest ways to create separation and position oneself to receive. As the ball is struck, he darts to the far post for a simple tap in.

Even though the goal is simple, it's the movement off the ball that's so impressive. It's an excellent example of understanding where the ball was when his teammate intended to cross, the priority of the defender to guard against a near post run, and the space available at the far post. Using numeric equality and a qualitative superiority to establish a positional superiority, Haaland's movement effectively dismarked him from the defender, leaving him unopposed at the far post. Again, a simple finish, but one that was set up by world-class movement off the ball.

Body Orientation

Step three concerns body orientation, which is the way we position ourselves to receive. A general rule of thumb is to maximize field vision and establish a forward-facing position as often as possible. Most have heard the saying, "play the way you face," but a better approach is to "face the way you want to play."

What's the difference between the two maxims?

Play the way you face is reactive. Your action is hostage to whatever conditions you've imposed on a given scenario. Facing backwards? Well, play backwards.

When we tell our players, "face the way you want to play," we're signaling that there's work to be done before they receive the ball. The emphasis is still on playing, but the second phrase refers to an off the ball action that is incomplete. There's still time to make an adjustment, time to correct our body orientation so that we can more effectively transition into our next action.

Ultimately, "face the way you want to play" encourages the players to make a decision, proactively engaging the game.

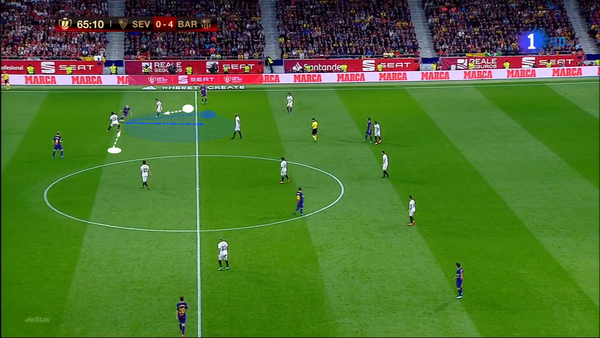

Good body orientation doesn't just result in movement and action efficiency; it also disguises intent, keeping opponents off balance. There's a great example of Andres Iniesta tormenting Sevilla back in his Barcelona days. As Iniesta received, he was 1v2 in tight space, but he was well aware of his teammates' support on either side of him. As you look at the image, both defenders have cut off the pass to those two players, but Iniesta's body orientation and brief moment of hesitation left his opponents unsure of themselves. Are we still cutting off those passing lanes? Sensing that moment of uncertainty and knowing that he had pinned his opponents, he split them on the dribble.

Again, a simple action, but it's the work he does before receiving the ball and with his first touch that creates the opportunity. The movement and first touch were not the ends in themselves, but, rather, a means of shifting the scenario in his favor. They were tools to unbalance the defenders, putting them on their heels and unsure of their orientation relative to the second attackers that allowed Iniesta to casually push the ball between them and win his 1v2 dribble.

If that Iniesta example shows you anything, it's that the movements and touches on the ball are simply the means to execute ideas. His objective was not to position himself away from the opponent and to attack space with his first touch. Those were simply the means. The objectives were to create a numeric superiority, produce an unbalanced movement from the defense, and break their pressure.

Mission accomplished.

It's that game inside the game that separates top players from the rest. It’s a search for the slightest advantages, their minds are actively looking for ways to create better attacking or defensive conditions for themselves and their teammates. They win their individual battles, often before the ball is even played to them. With the direct opponent beat, they attack the second defender, extending the first defender’s unbalanced state to a team scale.

We get an example of this from Kylian Mbappé. The Frenchman, as seen in the image below, has a side-on body orientation. That means his back is facing the sidelines. He can effectively move into higher or deeper positions, as well as dart inside. His first couple of steps are towards the ball, drawing the Brest right-back higher up the pitch, creating space to run behind the line.

We can quibble about whether he's facing the way he wants to play, but the general objective with this saying is to put yourself in a position to maximize the efficiency of your movement and action efficiency. He's done exactly that. Even better, he has disguised his intent, pulling his opponent away from the space he wants to attack. It's textbook execution.

Connect Your Actions

And that brings us to our final step for off the ball movement, which is to connect your actions. Once a player has found their space, filled it, and corrected his body orientation, the final step is to match the technical action to the context of the game.

Since the players have already done the bulk of the job through the first three steps, this should be the easiest of the four. With excellent spacing comes the time to fit the right technical action to the situation. Whether attacking space on the dribble or playing a first-time shot, receiving a pass with good spacing and body orientation allows the receiving player to move directly to his next action.

Let's not complicate this section. Instead, let's look at a couple of examples of players who did the work off the ball and reaped the rewards when they received.

The first is from Kevin De Bruyne. The Manchester City maestro produced a late equalizer against Liverpool, a brilliant bending shot to Alisson Becker's right, but we have to hit rewind and focus on the seconds leading up to the shot.

As you can see in the image, he is almost perfectly positioned between four Liverpool defenders. Given that this image comes just moments before his shot, you're right to assume that Liverpool has actually closed down a few yards of space at this point. At the time of the pass, he was in an even larger pocket of space at the top of the box. Manchester City's forwards did well to drive the backline towards goal, stretching the gap between the lines, but it's De Bruyne's presence of mind and discipline to pick out that spot that positions him for the first-time finish.

One touch. That's all that was needed.

De Bruyne’s off the ball movement positioned him to attack from a dangerous area, then his body orientation enabled the finish with his first touch. It's a magnificent example of spatial awareness and IQ in the flow of play.

Not all instances of movement and action efficiency are as elegant or spectacular as De Bruyne’s strike, but there's beauty in the simplistic too. Take Xavi vs AC Milan.

Initially, the Milan midfield stood between Xavi and the goal. Rather than forcing play forward or doing too much in possession, Xavi simply played a negative pass, then waited for the Milan midfield to run past him.

Look at the space he entered with very little movement off the ball. Further, you can see that he is prepared to receive on his back foot and run at the Milan backline. He has a teammate and an opponent to his right, which he can also use as a decoy for a more direct move up the pitch.

Xavi connected his actions by directing his first touch into the space he wanted to attack. But, again, that task would have been much more difficult had he not done the work off the ball first.

That negative pass wasn't just a means of retaining possession; it was a way to move the Milan midfield out of the space that he wanted for himself. Once he released the pass, he was free to roam about unmarked. Rather than prioritizing a passing lane to link up with the first attacker, he trusted his teammates to get the ball back to him in his preferred pocket of space. He wasn't ready to have the ball at his feet, so he released it to his teammates, trusted them to take care of it, and to return it to him once he was ready. With a better starting position behind the Milanese's midfield, his teammates understood he was ready. Game on.

Conclusion

Coaching movement off the ball is so difficult because you are training the player to understand his movement in a different light. Like moths, players are all too often drawn towards the ball, afraid to look away in the event that they'll be called into action. In doing so, players create their own blind spots.

And this is the way most, if not all of us, make our start in the game. Few are fortunate enough to break this bad habit, which complicates training sessions in the teenage and adult years.

But that is the task, breaking down the poor habits of our players and showing them the benefits and beauty of more intelligent play. We speak about off the ball movement not strictly in relation to the positioning of the ball, but in relation to the four reference points. In doing so, we expand our players’ field of awareness. We show them there's so much more to the game than just the positioning of the ball. It's but one reference point among many.

Knowing its gravitational pull, the ball is also our greatest weapon. We can use it to unbalance opponents, create attacking superiorities, and disguise our intent as we look to receive...and opponents will buy it. They'll buy almost every disguised intent because of their split focus between their own reference points, most demanding of which is often the ball.

So as we work on off the ball movement in our training sessions, we're not training predetermined A→B→C passing patterns that are only effective in shadow play exercises. We're teaching our players to move as a means of establishing advantages and negating disadvantages. We’re training patterns of relational superiorities and imbalances. We’re training players to autonomously create their opportunities for themselves and their teammates.

We move off the ball for a purpose, but only if we engage the game with purpose.